Stop 4b: Central Market

Central Market | 23 North Market Street

We will now turn our attention to the building nestled behind the imposing Griest building: Lancaster’s Central Market. Andrew Hamilton deeded this land to the City of Lancaster for the “Keeping, erecting, and holding a market” in 1730. Until 2005, it was the oldest publicly owned, continuously operating market in the United States. The building, designed by architect James H. Warner in a Romanesque style, was erected in 1889.

If you were an early riser, you might meet Demuth’s mother here. Marsden Hartley explained: “She went, formerly at least, with the manner of a lady who can trust no servant for qualities, to buy her own provender. She would be at the Mennonite market among the earliest, never later than six in the morning, because she wanted the dew on those fresh greens. …the greens were so precious looking they seemed more like corsages than edibles and a basket of them would have set a chef of the Cordon Bleu to gloating with culinary glee over them.”38

Left: Augusta Demuth. Richard W. C. Weyand collection of Charles Demuth. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Photographer Unknown. | Right: Charles Demuth, Augusta Wills Buckius Demuth, oil on canvas, 32 3/8" x 23 5/8", Demuth Museum Collection

Augusta Wills Buckius Demuth, (Mother Demuth or Dolly to her close friends and family), was “a tall, stately woman with a beautiful face and a clear voice like a bell. Mrs. Demuth had worn mourning ever since her husband’s death in 1911. Following Charles Death in 1935, she had double reason to wear it. As Elsie said: ‘He was all she had. Her grief must have been terrible to bear.’”39

Augusta and Charles: Richard W. C. Weyand collection of Charles Demuth. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Augusta was a strong willed and domineering woman, but with a sense of humor and a fondness for pranks. Her sister Kate would often walk over from the Buckius house on S. Queen street in the afternoon, when both Charles and his mother had the habit of lying down for a nap. Kate would bang on the back gate and holler “I know you can hear me, Dolly! Let me in!” while Charles and his mother lay in bed giggling and pretending not to hear.40 Robert Locher recalled the way Charles and Augusta would bicker back and forth constantly, but you could tell it was from mutual adoration.

Charles sometimes referred to her as “Augusta the Ironclad”, moving “like a ship under full sail”. She was thrifty and religious, with little apparent interest in life’s frivolities. Charles wrote to Alfred Stieglitz regarding a catalog for Stieglitz’s new show: “Mother said (out of the blue):’This—These are the only pictures I have seen since the Ryder show.’ It was such a strange remark from her. Of course, you don’t know her. She is not easily impressed, and I did not think very responsive to ‘art’, so called.”41

Augusta Demuth: Richard W. C. Weyand collection of Charles Demuth. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Augusta had a tendency to treat Charles like a child and referred to him in letters to others as “The Boy”.42 Perhaps she wanted him to remain the dependent little four-year-old who relied on her for everything. He certainly needed her after 1920, when he first showed symptoms of Diabetes.

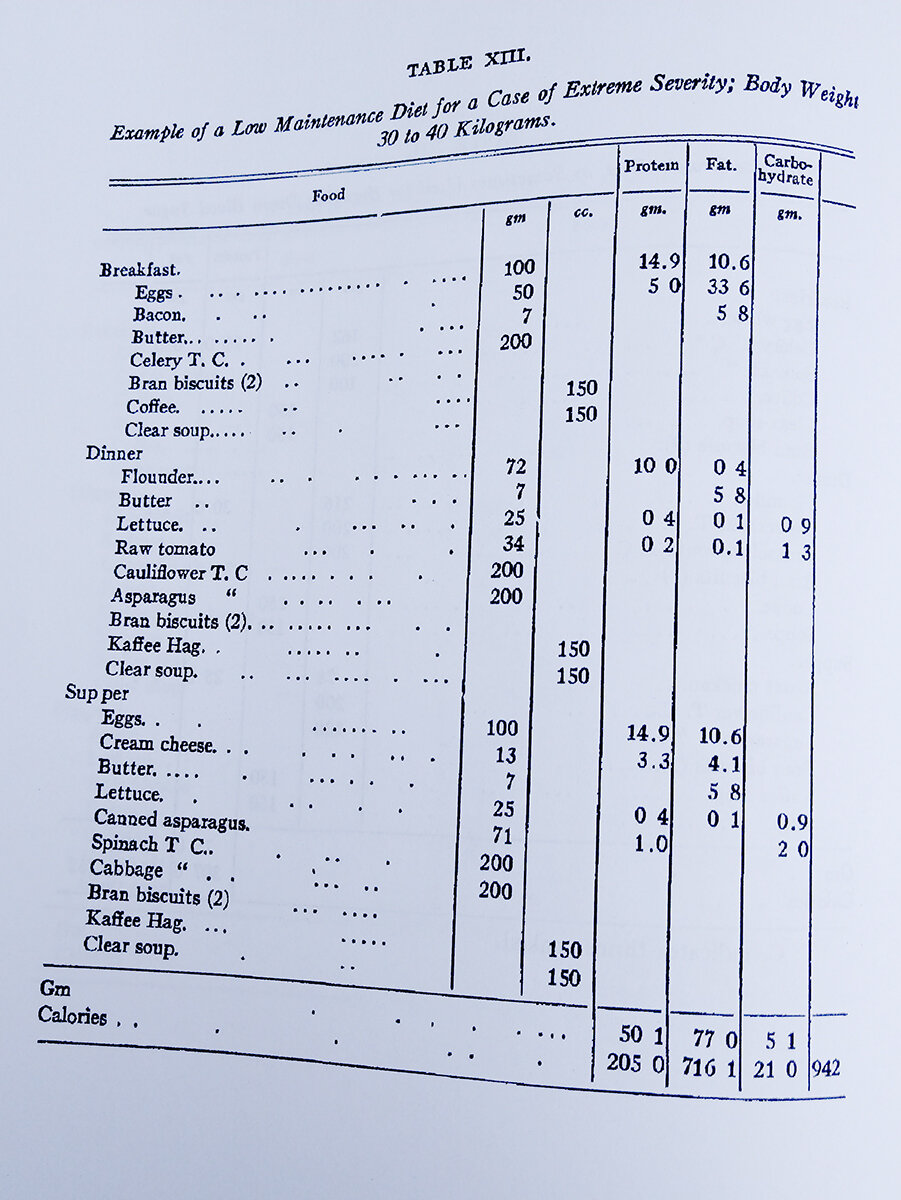

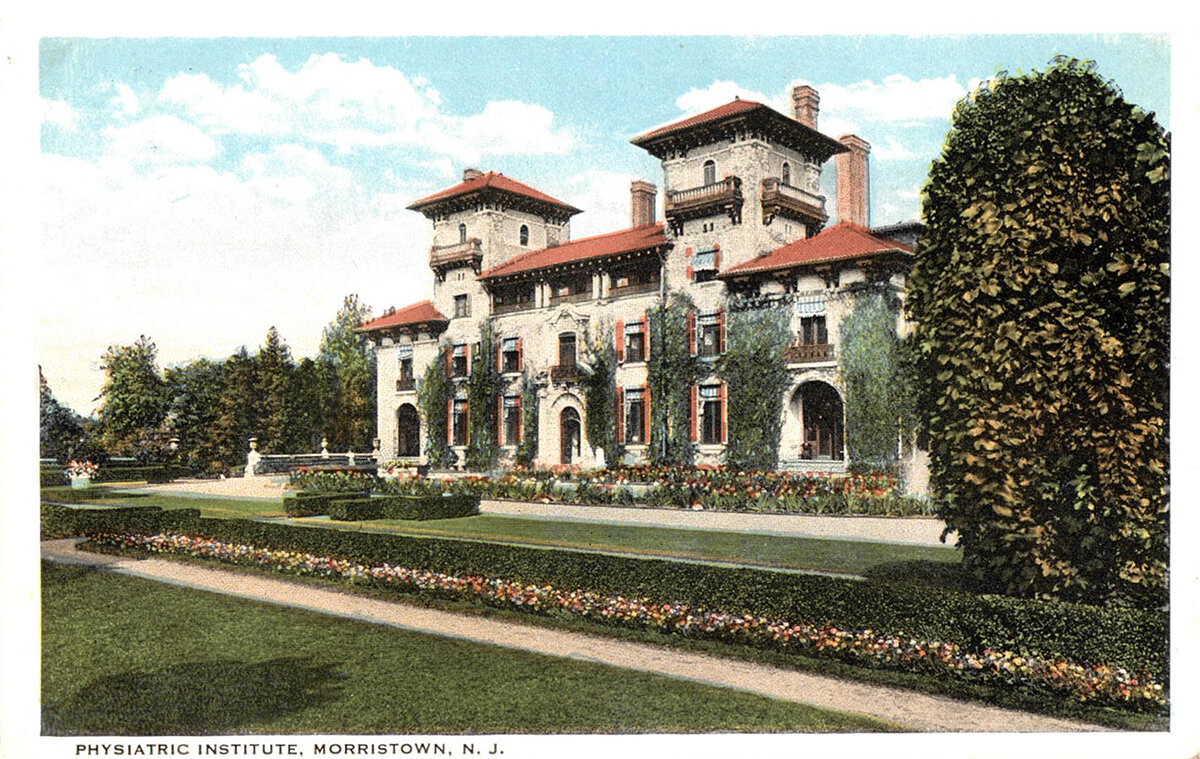

Fortunately, a sanitarium designed expressly for the dietary treatment of diabetes was established in 1921 at Morristown, NJ, in the old Otto Kahn house. And Augusta Demuth possessed the intelligence and means to take her son to Morristown, where he became one of the Physiatric Institute’s first patients.43 The standard treatment for Diabetes at this time, before the discovery of insulin, was a starvation treatment. The patient would be given 500 calories a day unless the blood sugar reached a normal level, then the food intake was slowly increased to about 1200 calories. Food had to be carefully weighed, and starchy vegetables avoided.

Demuth wrote: “Well, here I am finally put away, by my own hand. It seems very thorough!—well, rather,--but what, no doubt, I need. Very tiring,--although a wonderful place as to surrounding country…In time, I will get everything,--that seems the idea,--even sugar. Of course, so far I’ve been starved, that is egg and meat in very little quantities… I am bored stiff.”44

His friend Dr. William Carlos Williams wrote: “The result was frightening. Charley faded to mere bones, but he was able to live. They occasionally permitted him to be taken home to us for a short visit but I had to return him the same evening. He brought with him a pair of scales and weighed his food carefully. I never saw a thinner person who could stand on his feet and move about.”45 By July, 1922, Demuth wrote: “Am enclosing, I think, a very good report of myself (and garden)…hope you like it. Sorry I couldn’t do something for “M.S.S.” about camera. Couldn’t. Very little left after I do my daily (sometimes, now weekly) painting.”46 Charles was forced to face the fact that he was nearing the end of his life. “Today my food goes up,--then we will see,--will let you know. I think that I’ll be here, of course, for some weeks,--However, I’ll go through with it now,-- What else is there to do,--and I do think Allen is the real thing,--very unemotional and cold,--drives me almost mad at times,--best in the long run, I tell myself, in my sane moments.”47

Demuth in the Garden: Richard W. C. Weyand collection of Charles Demuth. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Photographer Unknown.

Fortunately, insulin was discovered in 1921 in Canada. It was in Morristown on August 10, 1922, that Dr. Allen first administered insulin in the United States.48 Demuth was reluctant to try the new treatment, but Dr. Barnes persuaded him to try it. Dr. Emily Farnham reported that Demuth was the second patient in the U.S. to receive insulin.49 By September, 1923, Demuth was able to write “On the other hand, I grow fat,--and fatter,--which is something! And I garden and cut grass and stay on the move,--as is expected, it seems.”50 This last comment seems to refer to Augusta, and her constant nagging.

Augusta resumed her role as Charles caretaker, carefully weighing his food and ensuring he followed his diet. Charles’ strength waxed and waned depending on the strength of the insulin batch, but he quickly tired. For this reason, he focused on watercolors, particularly the still-lifes of vegetables and flowers. He would meet his mother at the kitchen door, grab the market basket from her hands, and carry it up to his studio to paint them before she could start cooking. He would sometimes ask for Eggplants with a rich color and nice form.

Even after Charles death, Augusta would rise early to come to the market. One day in 1943, probably the morning of February 5th, while on her way to the Central Market, Mother Demuth was struck by an automobile in the fog and suffered a broken hip. She died two weeks later at the age of eighty seven.

Mother Demuth never returned to 118 E. King Street after setting out for the market on that day. After her death, relatives and friends discovered the touching perpetuation of Demuth’s life in his personal effects, meticulously preserved by his mother just as he had left them eight years before. Demuth’s [galoshes] were on the floor and his expensive coats on the rack in the front hall. Throughout the house all of the artist’s possessions had been retained in perfect order exactly as he had left them, even down to “the special tray for his diabetic syringe, with a white towel or napkin over it, which she [Mrs. Demuth] changed every week until her accident."51 It is sadly ironic that the “world famous artist”, the son she had dedicated her life to caring for and for whom she is now known by, wasn’t even mentioned in her obituary.

We will now head to the site of the 1912 Lancaster Portrait Show and discuss Charles’ reception as an artist in his hometown.

38 Hartley, Marsden. “Farewell, Charles”, The New Caravan. W.W. Norton & Co.: New York. 1936. P560.

39 Farnham. Behind a Laughing Mask. P.175

40 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, Vol.3, p.963

41 Kellner, Letters. P.52-53

42 Kellner: Letters. P.xvi

43 Farnham: Behind a Laughing Mask. P. 137

44 Fahlman, Betsy. Chimneys and Towers. University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia. 2007. P.80

45 Farnham: Behind a Laughing Mask. P.138

46 Fahlman: Chimneys and Towers. P.81

47 Fahlman: Chimneys and Towers. P.80-81

48 Fahlman: Chimneys and Towers. P.73

49 Farnham: Behind a Laughing Mask. P.138

50 Kellner: Letters. P56

51 Farnham: Behind a Laughing Mask. P.175-176