Stop 3: Demuth’s Tobacco Shop

Demuth Tobacco Shop | 114 East King Street

McBride wrote: “The Demuths, did I tell you? were the original snuff makers and the first tobacconists in America, starting in 1770, and the shop still flourishes next door. It is exceedingly elegant, being more artistic than Dunhill’s, or those other smart shops in London. The cousins run it. Charles disdains it, naturally, but his mother took me in when he wasn’t looking.”20

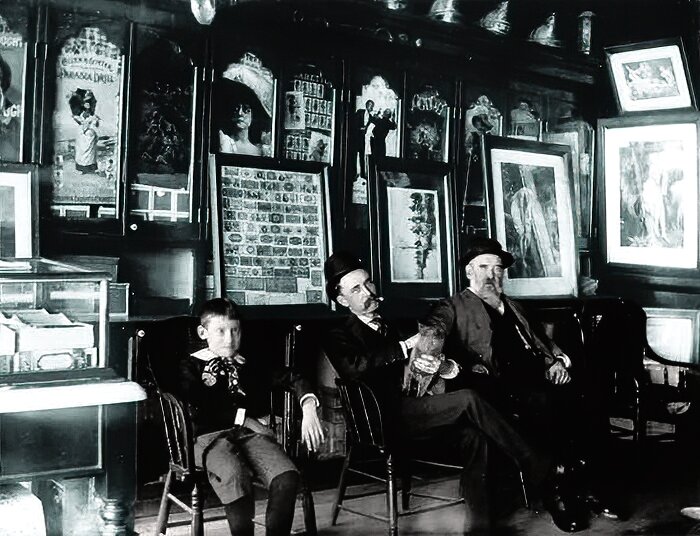

You can see from the photos the many art nouveau posters and other artwork in the tobacco shop which Demuth would have been exposed to from an early age.

Demuth’s ancestors arrived in Georgia from Germany as Moravian missionaries. The Royal Governor and other colonists did not appreciate their objections to taking up arms against the hostile native tribes, so they moved north to the more religiously tolerant colony of Pennsylvania. They helped found the town of Bethlehem, PA, which is where Demuth’s Great, Great Grandfather Christopher was born. Around 1769, Christopher Demuth moved to Lancaster following a scandal which forced him to leave Bethlehem. He married Ann Elizabeth Hartaffel, and in 1770 started this tobacco shop with his father-in-law William Hartaffel.

The shop stayed in the family for the next 227 years, being passed from Christopher to his son Jacob, to Jacob’s son Emmanuel, to Emmanuel’s brother Lawrence, Back to Emmanuel, then to Emmanuel and Lawrence’s brother Henry Charles Demuth (Charles Grandfather). In 1906, the business passed from Demuth’s Grandfather to his Father Ferdinand and his Uncle Harry. Ferdinand ran the Tobacco Shop while Harry managed the snuff and cigar factory on E. Mifflin Street. The Demuth brand of cigars were the "Golden Lion", and you will notice that the door to 116 East King Street, the residence of Charles' grandparents, and later his aunt and uncle and cousins, is painted gold with a lion door knocker.

When Demuth’s father passed away, his Brother Harry took over the business. Harry passed the business to his son Christopher, and when Christopher passed away, his wife Dorothea ran the shop until health issues forced her to sell the business. The shop continued to run under the name Demuth’s Tobacco until 2010, the oldest tobacco shop in the U.S.

Christopher Demuth: Courtesy of the Lancaster County Historical Society

Demuth’s was more than just a place to buy tobacco. Like restaurants, bars, and barber shops, it was a meeting place where people gathered to gossip and share the latest news. Its close proximity to the courthouse meant a steady stream of influential judges and lawyers visited. This contributed to the shopkeeper’s role in civic engagement and led several generations of Demuths to serve on the Chamber of Commerce.

Demuth and his Mother inherited Ferdinand’s share in the business, which they sold to his Uncle Harry for $6,000.00. This money was added to a $10,000.00 trust fund Ferdinand had established from which they received a monthly income. This, combined with Demuth’s aristocratic nature and taste for quality, led his friends to joke about Demuth being rich, about not needing to paint to pay the bills. Demuth was in on the joke, referring to his house as “The Chateau” and Lancaster as being “In the Province”. He wrote to Alfred Steiglitz in 1929 about one of his paintings: “I’d like to give it away—if I were really rich—to Georgia, or Robert, or Muriel, all having seemed enthusiastic about it.”21 Two years earlier, he had written: “You know that flower water-colour is still at Montross. If G’Keeffe really some time wants it, of course she can have it. I wish I could give them away to people who really like them & want them. It would make that part of art so much simpler. These terrible Daniels, etc., of our world.”22 He was distrustful of art dealers and hated the commercial side of art. He wrote to Stieglitz: “I hope someone opens a gallery in New York. I feel that Daniel is a crook,-- a nice fellow but a crook,-- I can’t cope with it any longer.”23

Art critics like Henry McBride and others picked up on this, and often commented that Demuth’s financial security held him back as an artist. McBride wrote: “I think that having money is more of a handicap than it is an asset to an artist. At least, that’s been my observation. I have known a number of well-to-do artists who just never made the effort that one must make to get anywhere. … Demuth didn’t push.”24 “The unfortunate thing about Demuth’s work is that it reveals in the artist a contentment with his tricks and mannerisms, and a lack of striving for more solid and masculine attributes.” Willard H. Wright added.25 The next year, Demuth exhibited a painting titled "Box of Tricks."

Charles Demuth, Box of Tricks, 1919, gouache and graphite on cardboard, 19 7/8" x 15 7/8", collection of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, acquired from the Philadelphia Museum of Art in partial exchange for the John S. Phillips Collection of European drawings

The truth is that, while he was comfortably in the middle class, he was far from rich and occasionally had to beg friends like Dr. Albert C. Barnes for loans. Charles had to work for a living, something he was deeply ambivalent about. He wrote in a letter: “I like few places and few people but see them seldom. Perhaps I wouldn’t work at all if I did.”26 The alternative to work, however, was boredom. “Ennui is a reckless state—perhaps the most reckless” Demuth writes in “The Voyage was Almost Over”.27 This may indicate that Demuth was prone to periods of introspection which led to depression when he was not occupied with work. So Demuth settled into a lifelong pattern of traveling to New York, Provincetown, and Paris for inspiration, then returning to Lancaster where he would closet himself in his studio like a monk and paint. Demuth wrote: “So few understand Love and Work; I think if a few do, we may not have lived entirely without a point.”28

We will now head to Penn Square to meet Demuth’s parents.

20 Watson & Morris, An Eye On The Modern Century, p.169

21 Kellner, Letters, p.117

22 Kellner, Letters, p.98

23 Kellner, Letters, p.20

24 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works, p.982

25 Kellner, Letters, p.147

26 Demuth Museum Didactic panel

27 Farnham, Life, Psychology, and Works. Vol. 3., p.925

28 Kellner, Letters, p.20